Who Wants a Pope?

Coline Milliard explores the pop world of the late Ray Johnson, founder of mail art & an artist currently receiving critical reappraisal

To begin researching American artist Ray Johnson, aka ‘the father of mail art’, means to be confronted immediately with apocryphal literature, unverifiable rumours, friends’ emotional recollections and the artist’s ambiguous quotations, all of these repeated and transformed ad infinitum in a strange game of Chinese whispers. While Johnson is a seminal figure, venerated by an underground network of mail artists, he remains relatively overlooked by the ‘official’ contemporary art world. Perhaps by choice, perhaps by lack of luck, most probably a mix of the two, he only occasionally exhibited his intricate collages in galleries and museums during his lifetime, preferring instead to disseminate them through the postal system.

It was only after Johnson committed suicide in 1995, aged 67, that institutions really began to take notice of his work and legacy. By now numerous shows have been organised worldwide and in February this year, Alex Sainsbury chose to inaugurate his new London art foundation, Raven Row, with an extensive exhibition dedicated to the artist.

For all those who, for years, have been actively promoting Johnson’s work, this belated recognition may feel like some kind of vindication. But it’s likely that many of his followers won’t much enjoy the fact that their mentor is now gradually accessing the place he deserves in art history. Much of the man’s legendary status is supported by his ‘outsider’ credentials; even during his lifetime he inspired idolatry among many of his contemporaries. In, 2003, John Walter and Andrew Moore’s film on the artist, Norman Solomon recalls compulsively photographing Johnson between 1952 and 1956, when he was living in the same Monroe Street apartment building as John Cage. During our interview, Johnson’s close friend (and main lender to the Raven Row exhibition) Bill Wilson admitted starting an obsessive study of the artist’s life as early as 1956: ‘I asked for things out of the trash basket’, he remembers.

And Johnson’s following, sometimes irrational, fan-like, kept growing after his mysterious death. ‘Ray dies’, says Wilson, ‘and an artist whom I’d become friends with publishes a limited edition number of pamphlets and says Ray was, “a half god, and the Pope of mail art”. I answered with a very violent letter – who wants a pope? No, he is the father of a network of mail artists, and that’s the important thing.’

Born in 1927 in Detroit, Johnson enrolled at Black Mountain College at the age of 21, studying under Josef Albers, Robert Motherwell and John Cage, and rubbing shoulders with future greats of the New York avant-garde, including Cy Twombly, Robert Rauschenberg and Kenneth Noland. Leaving Black Mountain in 1949, he moved to New York, where he became a feature of the art scene alongside artists like Andy Warhol and Billy Name. Johnson had trained mainly as a painter, and at first worked on colourful abstract canvases of meticulously arranged stripes and squares, demonstrating an adherence to his teachers’ modernist formal principles.

But this style was soon abandoned, and in the mid-1950s Johnson famously, or mythically, burnt all his previous works in Cy Twombly’s fireplace, also ridding himself of all his old art supplies, brushes and paint in order to make the cleanest possible new start. If vastly different in content and tone, the multi-layered collages of newspapers and magazines that followed soon after (and which were to become Johnson’s signature creations), share with the early paintings, qualities that run through the artist’s entire body of work: a strict sense of composition and the repetition of organisational grids.

But if this analysis suggests coherence, it conceals what was, from this point on, the artist’s cultivation of the enigmatic. While building an enormous body of collages, all puns and subtle image associations, Johnson simultaneously provided his admirers with unusable classifications and clues, as if to undermine the very ideas of artistic categorisation and linear development. Some of his works, for example, were dubbed ‘moticos’, a word of Johnson’s invention that some explain as encapsulating a sense of movement, flux and transformation (all concepts crucial to Johnson’s practice).

Today however, as most likely then, few are really sure what ‘moticos’ are: different factions variously apply the term to the artist’s first series of collages, which incorporate images of Elvis and James Dean, to his collages of irregular shapes, or to the glyph-like symbols that Johnson introduced in many of his pieces. The artist’s text ‘What is a Moticos’, a poetic plea for the artwork as an entity existing outside the constrained atmosphere of the gallery space and enmeshed within the urban fabric, doesn’t really provide any tangible explanation, if one were possible. The label ‘moticos’ may have encapsulated, for the artist, something that goes far beyond a certain set of artworks; perhaps it stands for an attitude toward the art, freed from its display conventions. This indeterminacy is typically Johnsonian. By design or not, the artist was constructing his own myth.

In the 1950s, Johnson recurrently used images of pop icons. This has lead to heated and largely pointless discussions around the identity of the ‘real’ inventor of pop art. These debates have often missed a capital distinction between Warhol and Johnson’s appropriation of mass-produced images of celebrities: while Warhol turns Marilyn and Elvis into empty representations of glamour and fame, Johnson seems to identify with them, project himself onto them. Like the countless self-portraits he later introduced in his collages, these images were a way for Johnson to assert his own presence, attractive and desirable, within his own works.

Besides, Johnson’s use of these images, cut out, partly covered, layered with other material, has more to do with Rauschenberg’s textured canvases than with Warhol’s clinical, willingly soulless silk-screened reproductions. Warhol thrived on removing anything remotely emotional, but Johnson’s treatment of celebrity images remains sensual and lyrical. This is especially visible in ‘Elvis #2’, 1956-57, perhaps one of the most famous of Johnson’s early works. The androgynous dandy’s face is covered in raw red stamp-like squares; he looks like he’s been skinned, revealing the fleshy meat under his pretty features. Two holes, directly cut into the piece, turn it into a mask, a cover potentially both concealing the artist’s face and revealing some truth about him.

Early on, Johnson was faced with the problem of distribution. Later he claimed that it was simply because he didn’t know what to do with his collages that he started to stuff them into envelopes and mail them to everybody he knew, but the reality probably isn’t that simple. There is, for instance, a clear distinction between the large, heavily worked out collages that were meant to be sold or at least shown in galleries, and the quick and witty cut-outs and Xeroxes that formed most of Johnson’s correspondence. The two are by no means interchangeable, and each piece was clearly made with one or other of these purposes in mind.

The artist had a few solo exhibitions in New York in the 1960s and early 1970s, but not nearly enough to satisfy both his yearning for attention and his practical survival. Mail art is often explained along the lines of hippie-ish, gift-based relationships co-opted by the mail art network that formed in Johnson’s wake (and is estimated today to comprise between 10,000 and 50,000 members, depending who you are talking to), but it is very likely that Johnson started to exchange mail art not to give or exchange, but to receive. ‘My correspondence art only existed for one person – me’, the artist said. It was an alternative system of distribution which allowed him to bypass the institutions from which he felt excluded: ‘Dear Whitney Museum, I hate you, Love, Ray Johnson’, reads one of his pieces in the Raven Row exhibition. This way he sought to reach hundreds, if not, thousands of people for, despite what is often repeated, this network was not only made up of his friends: Johnson was a canny operator, targeting also critics, museum curators and famous artists, and corresponding with these art world personalities was a way for him to force the door to their world. In 1991, Chuck Close was invited by the Museum of Modern Art, New York, to curate an exhibition with works from the collection. ‘It’s too bad they don’t have anything of yours’, he said to Johnson, who, aware of the fact that the museum kept everything that was sent to the library, soon flooded the MoMA librarian with mail art. Close was then able to choose a piece by Johnson which technically belonged to a MoMA collection, albeit the library’s.

Johnson’s New York was dominated by abstract expressionism and the emergence of Rauschenberg and Warhol’s pop and Maciunas’ fluxus, both of which quickly gained international attention. But while Johnson was often around these movements’ main protagonists, he refused to be assimilated into any of them. In 1962, Ed Plunkett, an artist Johnson had been corresponding with for some time, coined a term for the network of people with whom Johnson regularly exchanged postal art; the New York Correspondance School (sic), was a pun on both the New York School of painting and the then-flourishing trade of correspondence-based art instruction. This ‘school’ was only materialised by exchange between the participants, but it became Johnson’s base, his own artistic movement, and a platform from which to claim his difference from pop and fluxus, already on the brink of becoming celebrated and mainstream.

In 1968, on the same day Warhol was shot by Valerie Solanas, Johnson was mugged in New York, and he decided to leave the city. The artist moved to Glen Cove, and then in 1969 to Locust Valley, Long Island, and what he called ‘a small white farmhouse with a Joseph Cornell attic’. From then on he socialised very little but remained nonetheless the nexus of the Correspondance School, producing all the while an enormous quantity of works, most of which where discovered after his death, neatly stacked up in his house. Magazine and newspaper snippets were not his only materials; Johnson often cut up his previous works and added their morsels to works in progress.

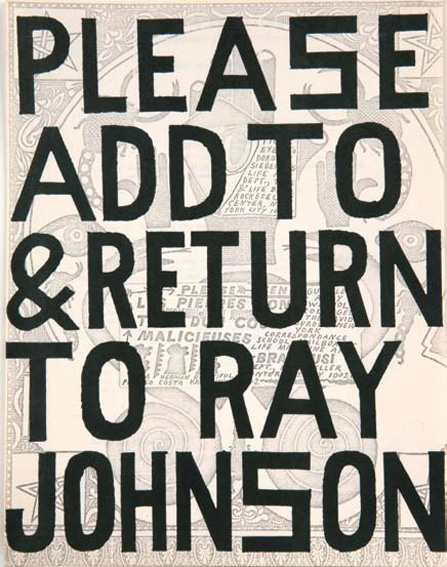

He continued to work on pieces over very long periods of time. ‘Silhouette University’, for instance, is inscribed 1977-80-86-88. His correspondents too, were also frequently encouraged to interact directly with the work, and the words ‘PLEASE ADD TO AND RETURN TO RAY JOHNSON’ were a regular feature of the artist’s mail art, a particular twist on the idea of viewer/ participant very much in vogue in the mid-century avant-garde milieu.

‘Ray had profound ambivalence about everything, even about living’, said Chuck Close in a panel discussion shortly after the artist’s death. ‘He wore his outsider status both as a badge of honor, and he also was incredibly pissed-off. He made things difficult, and yet he wanted attention desperately.’ Johnson craved recognition, hassling friends to buy his works, yet he turned down many opportunities for much greater visibility, playing cat and mouse with his dealer, collectors and galleries. His move to Long Island was perhaps a way to remove himself from that game, and to advertise his non-interest in the race to stardom. As is often said, Johnson constructed his own life, and his death, like an artwork, setting up roles for himself, creating and embodying characters. Since he wasn’t going to be an art superstar, he would become the romantic, undiscovered genius.

The choice of this persona is crucial to the fervour of his art-outsider admirers who, by choosing him as their mentor, have also established themselves as superior to the institutions who failed to recognise his talent. Today’s reappraisal of Johnson’s work within the framework of institutional art history, emblematised by exhibitions such as the one at Raven Row, opens a fascinating new chapter in the artist’s exegeses, away from the ‘we-knew-betters’ and ‘whodid- it-firsts’ that have up to now constituted such a large part of the Ray Johnson story.

Coline Milliard is a writer living in London

Ray Johnson, Raven Row, London, 28 February-10 May Ray Johnson… Dali/Warhol/and others, Richard L Feigen & Co, New York, 29 April-31 July