The fact that we do

Joanna Peace writes on EVA International in Limerick in the context of the Irish Referendum

We are riding the bus from Dublin airport into the city. Punctuating my view from the top deck are colourful campaign placards strung at eye height on every lamppost. As we travel through the concentric circles of industrial estates, suburban housing, busy high streets and wealthy neighbourhoods, these placards feel like an unpredictable threat, oscillating between messaging that is gentle and reasonable, and visual and textual material that feels deliberately upsetting and provocative. As we reach the city centre, the placards grow in number, swarming the full height of lampposts and covering the sides of buildings in loud mid-air broadcasts. I had been warned about the aggressive nature of this very public debate but still, the shock of the language and imagery leaves me tenderised. Raw.

*

I have found myself witness to an excessive number of referenda in recent years: Scotland in 2014, Greece in 2015, and then Scotland again in 2016. While all three would have profound effects on the citizens of the UK, Greece and beyond, none have felt as close to both my own and to thousands—millions—of other women’s biographies, as the Irish referendum this year. This referendum, held on 25th May 2018, was to decide whether the eighth amendment to the Irish constitution, which all but prohibits abortion in Ireland, was to be repealed or remain in place. This momentous opportunity was the reason for my visit to Ireland, so that my partner could cast his vote. It also happened to coincide with the 38th edition of EVA International, Ireland’s biennial of contemporary art, in Limerick.

While in Ireland, I found I wanted to attend to the ways in which the referendum was composing itself in public space, and to listen carefully to what was being shared in private spaces. These accumulating narratives were at times overwhelming. Winding through the multiple venues of EVA, I found myself drawn to works that echoed my state of sensitivity, works that evoked parallel narratives of bodily autonomy, or lack of. While beyond the walls of the biennial raged a debate in which the female body was being reduced both to a generic body and welcomed into a sense of active collectivity, these works addressed the appropriation of the body for political agendas and ideologies, for national memory and artistic expression.

*

Walking along the River Shannon, lazily making her way through the city, we arrive at the first venue, Cleeve’s, a former condensed milk factory. Entering the large quad, ringed by dilapidated industrial buildings, it is strangely easy, on first glance, to overlook ‘Lady Rosa of Luxembourg’ (2001). From her perch on top of a plain-timbered obelisk, an 8ft statue of a woman looks down on us, golden, pregnant-bellied, draped in thin fabric with arms outstretched holding a circular wreath. At the obelisk’s base are capitalised words shouting in French, German and English: LA RÉSISTANCE, LA JUSTICE, LA LIBERTÉ; KITSCH, KULTUR, KAPITAL; WHORE, BITCH, MADONNA.

This work by Sanja Iveković was first sited in Constitution Square in Luxembourg in 2001, where it shared the city’s skyline with the monument it mimics—a war memorial popularly known as ‘Gëlle Fra’ (golden lady). The original Golden Lady is a larger-than-life neoclassical Nike—the allegorical figure of victory—first erected in 1923 and later taken down by the Nazis during their occupation to languish, hidden, before being uncovered and resurrected in 1985. Iveković’s replica gives Nike a pregnant belly and is dedicated to Rosa Luxemburg, the writer and activist murdered in 1919.

The effect that ‘Lady Rosa’ had on her original audience—with responses ranging from outraged, to dismissive and humorous—is documented by the accompanying contextual material housed in a nearby shed. Protests that verge on the violent are shown alongside a satirical play of two women acting out the statues in dialogue, and an interview with the artist on mainstream TV. Yet, sited by EVA behind the high walls of the old factory on the edge of the city, removed from its site-specificity, the work loses some of its agency. The original installation instigates a dialogue with the history of Luxembourg, it acts a provocative lance to old wounds and a public focus for histories still affecting the present, in the way that much of Iveković’s work ‘drags the specters out into the light and allows us to confront them’ [1]. In Cleeve’s, ‘Lady Rosa’ appears to have become a monument to herself as a work of art, untethered from the time and place from which her power derives.

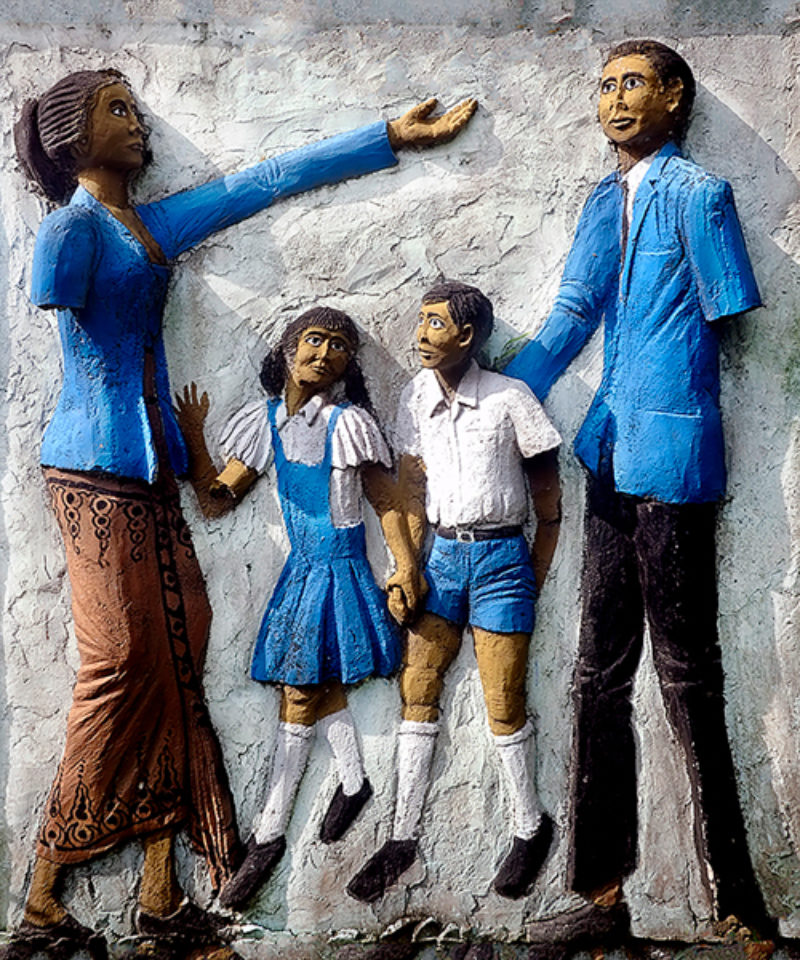

Much like ‘Lady Rosa’, the reliefs and sculptures repeated within Akiq AW’s ‘Indonesian Family Portrait Series’ (2016-17) are less portraits than allegories, repurposed by the artist as conduits for a collective memory. Depicted within each photograph are similar imaginings of a ‘nuclear’ family; the poses, colouring and representational style may vary, but each includes one man and one woman, flanking a boy and a girl.

These figures are the spectral remains of the Indonesian state programme Keluarga Berencana (Family Planning) begun in the 1970s as part of the New Order Administration. The programme set out to better control the national birth rate, and these reliefs, statues and gates depicting the ‘perfect’ family were their promotional material, visible in every neighbourhood and at every village entrance. Mounted in a grid on an external wall of Cleeve’s factory complex, the strangeness of this work lies in its repetition, triggering comparisons with the images of normative familial happiness that pepper our online and print media.

The first works visible upon entering the Limerick City Gallery of Art are paintings by Seán Keating depicting the construction of the Ardnacrusha Power Station, a hydroelectric dam on the River Shannon that became a symbol of Ireland’s newly gained independence in the 1920s. One of these was chosen by curator Inti Guerrero as the starting point for EVA 2018, around which he gathered a constellation of works that address themes of power, technology and spirituality. In ‘Night’s Candles Are Burnt Out’ (1928-29) by Keating, Ardnacrusha becomes the backdrop for a collection of allegorical figures: a priest, a businessman, a soldier, a drunk and a young family, representing Ireland past and future at a moment of national transition.

Keating’s paintings of the dam’s construction emanate a forceful energy: machinery and labourers move earth and water, bringing them under the control of the nascent nation state. The wielding of power and forms of resistance to it characterises works in the surrounding galleries. The video ‘Chandelier’ (2001) documents a performance by Steven Cohen that takes place amongst a homeless settlement in Johannesburg. As day turns to night, the camera follows a white man in sheer stockings, elaborate make-up and perilously high heels, wearing a corset that holds a glistening crystal chandelier around his torso. Cohen tentatively steps through the debris, contorting himself into attitudes of prayer-like vulnerability on legs that shake with the effort of remaining upright. The chandelier delicately tinkles, while around him the settlement is systematically dismantled by the authorities.

The video is mesmerising, but ultimately troubling. Cohen greets the inhabitants of the settlement with an almost provocative passivity, while their reactions vary from aggression to amusement to a protective care, with one woman offering a steadying hand, another getting in between Cohen and a man violently wielding a stick. It was in these moments of encounter that the work began to transcend its aestheticised theatricality. Despite this, the imbalanced privilege of the bodies captured by the camera’s gaze cannot be ignored.

In the upper galleries, among a number of works that deal with borders both physical and metaphysical, is David Pérez Karmadavis’ ‘Estructura completa’ (2010). In this video we see a blind man holding in his arms a woman who has had both legs amputated, and we follow them as they move through the streets of Santiago. We are told that the man is Dominican and the woman Haitian, that one speaks Spanish while the other Creole Haitian. Without recourse to a shared language, they interdependently navigate the obstacle-strewn pathways of the busy city, one acting as visual guide, the other as physical support.

Pérez Karmadavis is acutely aware of the entrenched conflict between Dominicans and Haitians, citizens of a shared island, and in this work the body again becomes allegory through a performance of cooperation. The unfolding of a symbiotic—rather than an exploitative—relationship between the two individuals on the screen, with all its visible tensions and risks, is moving. In this demonstration of pragmatic intimacy, I am reminded that care is not passive, and that ‘if we care, perhaps things can turn out differently’ [2].

*

On the day of the referendum vote we climb a high green hill outside of Limerick. Walking slowly and steadily, the path winds around to reveal a large body of water sitting serenely in the valley. It is warm and sunny, and as we put one foot in front of the other we gently and hopefully discuss the vote’s possible outcomes. That night we sit in the garden, and at the moment we hear that the referendum has almost certainly been won in favour of the repeal, a line of cars trailing lights across the bridge over the River Shannon all start beeping their horns. This joyful noise filling the dark valley feels portentous [3].

Because of the nature of this referendum, the moment of the repeal passing does not immediately feel like an opportunity for unbridled celebration, but rather deep gratitude that life in Ireland had profoundly changed for the better. These sentiments are reflected in much of the news coverage in the following days. While the repeal rightly affirmed Irish women’s right to make decisions about their own bodies, it was also a time to remember the suffering of women who had gone before, and to be thankful for the untiring work and bravery of so many who had shared their own stories throughout the campaign.

The power of storytelling was very present in the one artwork in EVA that, I must confess, I could not bring myself to experience fully. The Artists’ Campaign to Repeal the Eighth Amendment was established as an online appeal in 2015, asking for support for their call for repeal. Since then they have staged actions, held ‘A Day of Testimonies’, and for EVA organised a procession through the streets of Limerick. The colourful marching banners from that day are hung within an information hub at Cleeve’s, and the audio and video testimonies of women, performed by actors, ring through a warren of small rooms. Listening to those testimonies was just one act of witness too many for me, on that day, although my partner found it a deeply emotive experience.

*

As I write, reproductive rights are still being gained and lost: we only have to look to Argentina, whose congress approved a bill to legalise abortion in June this year, or to the US, whose increasingly conservative institutions are actively threatening women’s rights. During times when change is needed, and yet can seem so hard to imagine, let alone enact, we find ourselves looking for signs, evidence from the past and present that show us that things have changed, can change. Sometimes art can do this job of attending to the past and present for and with us. In creative acts of embodiment and imaging, the forces of power that move us take on ‘form, texture and density so that they can be felt, imagined, brought to bear or just born’ [4]. The bodies of artists, their collaborators and subjects, become stand-ins for our bodies, rather than for the bodies of the state or the church, in the same way that activists occupy public space on behalf of their communities.

Bringing certain histories into the present, making them audible and visible, can be painful. Yet, as the outcome of Ireland’s referendum makes apparent, it can ultimately be worthwhile, breaking silences and patterns of trauma, and lifting away shame. I take great comfort from repeating the words of poet Ariana Reines when she says, simply, that ‘the proof that we can change is in the fact that we do’ [5].

[1] Charles Esche, quoted in Carol Kino, ‘Croatia’s Monumental Provocateur’. The New York Times, 2011

[2] Laura Bissell et al, ‘Afterword: Acts of Care’. Scottish Journal of Performance, Volume 5, Issue 1, Art of Care, 2018

[3] We later found out that the cars were really beeping because Munster—the provincial rugby team—were in town! It didn’t spoil the memory though.

[4] Kathleen Stewart ‘Atmospheric Attunements’. Rubric, Issue 1, 2010

[5] Ariana Reines, ‘Festina Lente’. Artforum, 2018

***

EVA International, Ireland’s 38th Biennial, took place in Limerick City 14 April - 8 July 2018.

Joanna Peace is an artist, writer and educator based in Glasgow.